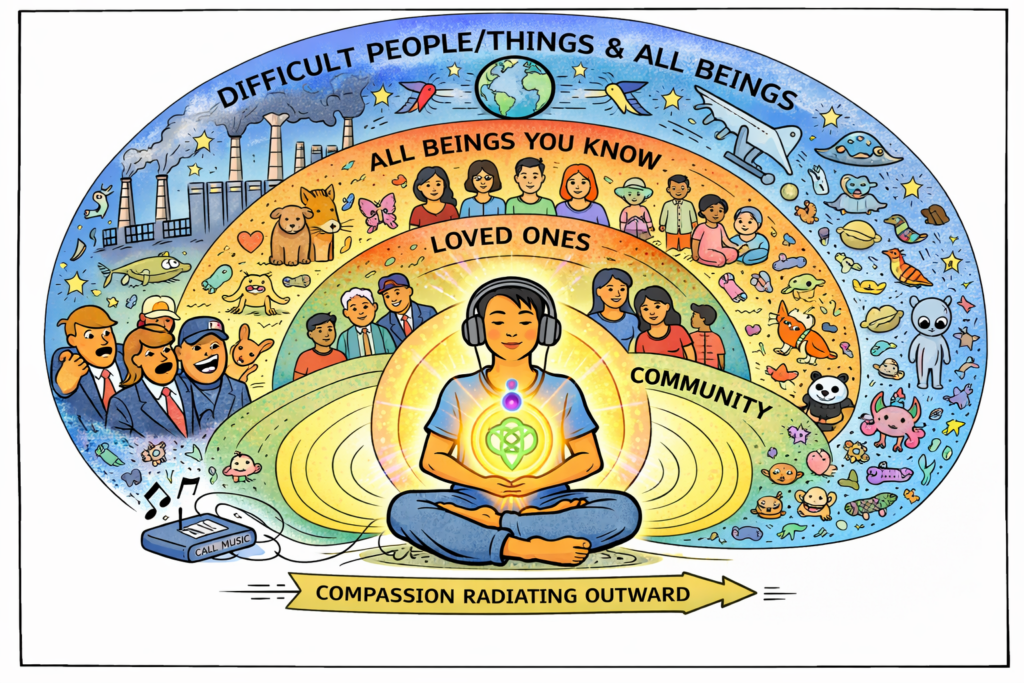

Making Self-Transcendence and Transformative Insight Accessible: Using Chills-Evoking Music to Enhance Meditation

Get The Article Article PDF Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Christov-Moore, L., Schoeller, F., Von Guttenberg, M., Durinski, T., Jain, F. A., Iacoboni, M., & Reggente, N. Using Chills-Inducing Music to Augment Self-Transcendence, Emotional Breakthrough, and Psychological Insight During Mindfulness and Loving Kindness Meditation. Frontiers in Psychology, 17, 1589132. Christov-Moore, Leonardo, et al. “Using Chills-Inducing Music […]

Extremely Chill Politics: Individual differences in aesthetic experience point to the role of bodily awareness in political orientation

Get The Article Article PDF Political Psychology Article Individual differences in aesthetic experience point to the role of bodily awareness in political orientation Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Christov‐Moore, L., Schoeller, F., Vaccaro, A. G., Pluimer, B., Iacoboni, M., Kaplan, J., & Reggente, N. (2024). Individual differences in aesthetic experience point to the role […]

The Thermodynamic Relationship Between Emotions, Motivation, and Time Perception

Get The Article Article PDF Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Christov-Moore, L., Schoeller, F., Von Guttenberg, M., Durinski, T., Jain, F. A., Iacoboni, M., & Reggente, N. Using Chills-Inducing Music to Augment Self-Transcendence, Emotional Breakthrough, and Psychological Insight During Mindfulness and Loving Kindness Meditation. Frontiers in Psychology, 17, 1589132. Deli, Eva, et al. “Feeling the Heat: […]

Aesthetic chills mitigate maladaptive cognition in depression

Get The Article Article PDF BMC Psychiatry Article Aesthetic Chills Mitigate Maladaptive Cognition in Depression Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Schoeller, F., Jain, A., Adrien, V., Maes, P., & Reggente, N. (2024). Aesthetic chills mitigate maladaptive cognition in depression. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05476-3 “Aesthetic Chills Mitigate Maladaptive Cognition in Depression.” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. […]

VR for Cognition and Memory

Get The Article PDF Paywalled Chapter VR for Cognition and Memory Cite This Work APA AMA MLA Reggente N. (2023). VR for Cognition and Memory. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences, 10.1007/7854_2023_425. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2023_425 Reggente N. VR for Cognition and Memory [published online ahead of print, 2023 Jul 14]. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2023;10.1007/7854_2023_425. doi:10.1007/7854_2023_425 Reggente, […]

Is Cannabis Psychedelic?

Get The Article Psychology Today Article Neuropsychopharmacology Article Is Cannabis Psychedlic? Neural complexity is increased after low doses of LSD, but not moderate to high doses of oral THC or methamphetamine Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Murray, C. H., Frohlich, J., Haggarty, C. J., Tare, I., Lee, R., & De Wit, H. (2024). Neural […]

Surprising new research reveals how fetal brain complexity declines before and after birth

Get The Article PDF Nature Mental Health Article Sex differences in prenatal development of neural complexity in the human brain Sex differences in prenatal development of neural complexity in the human brain Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Frohlich, J., Moser, J., Sippel, K., Mediano, P. a. M., Preissl, H., & Gharabaghi, A. (2024). Sex […]

Individual Differences in Aesthetic Chills

Get The Article Article PDF Scientific Data Article ChillsDB 2.0: Individual Differences in Aesthetic Chills Among 2,900+ Southern California Participants Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Schoeller, F., Moore, L., Lynch, C., & Reggente, N. (2023c). ChillsDB 2.0: Individual Differences in aesthetic chills among 2,900+ Southern California participants. Scientific Data, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02816-6 Schoeller, Felix, et al. “ChillsDB […]

Predicting Chills – Characterizing Individual Differences in Peak Emotional Response

Get The Article Article PDF PNA Nexus Article Predicting individual differences in peak emotional response Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Schoeller, F., Christov-Moore, L., Lynch, C., Diot, T., & Reggente, N. (2024). Predicting Individual Differences in Peak Emotional Response. PNAS Nexus, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae066 Schoeller, Félix, Leonardo Christov-Moore, et al. “Predicting Individual Differences in Peak Emotional Response.” PNAS […]

The neural correlates of chills: How bodily sensations shape emotional experiences

Get The Article Article PDF Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience Article The neurobiology of aesthetic chills: How bodily sensations shape emotional experiences Cite This Work APA MLA Bibtex Schoeller, F., Jain, A., Pizzagalli, D. A., & Reggente, N. (2024). The neurobiology of aesthetic chills: How bodily sensations shape emotional experiences. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-024-01168-x […]